Published on 19 Oct 2020 in agile

Learning how to identify decisions that can be made quickly and making them decisively can make a huge difference in your personal and business life.

You can’t rush some decisions. Most people rightly wouldn’t buy a house on the spur of the moment. Likewise in business many decisions have huge implications and take time to fully consider. The problem is that sometimes we go too far; we slow ourselves down by failing to recognise the decisions that can be made quickly. We miss out on a first mover advantage, the learning from doing and any benefit we’d be getting from the change.

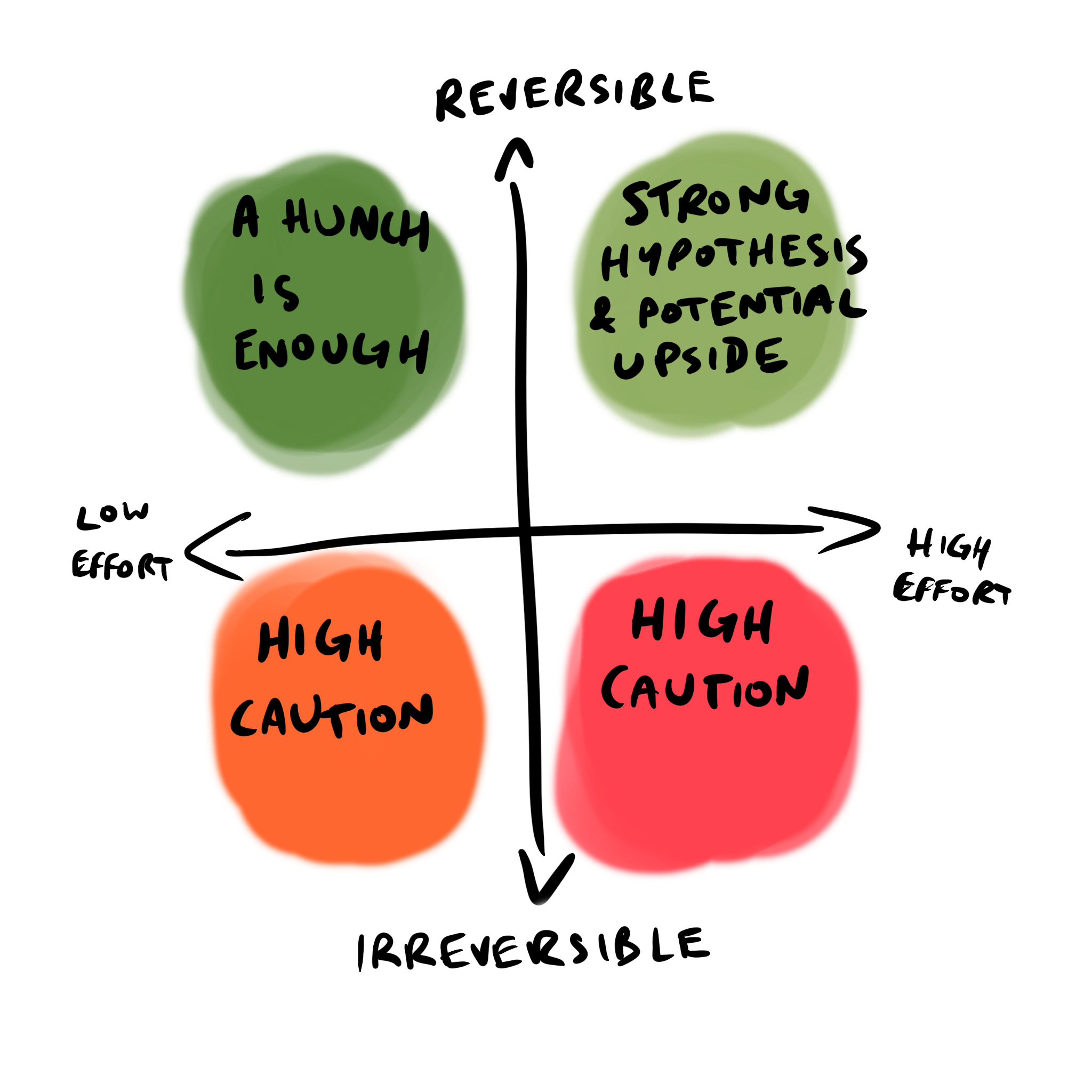

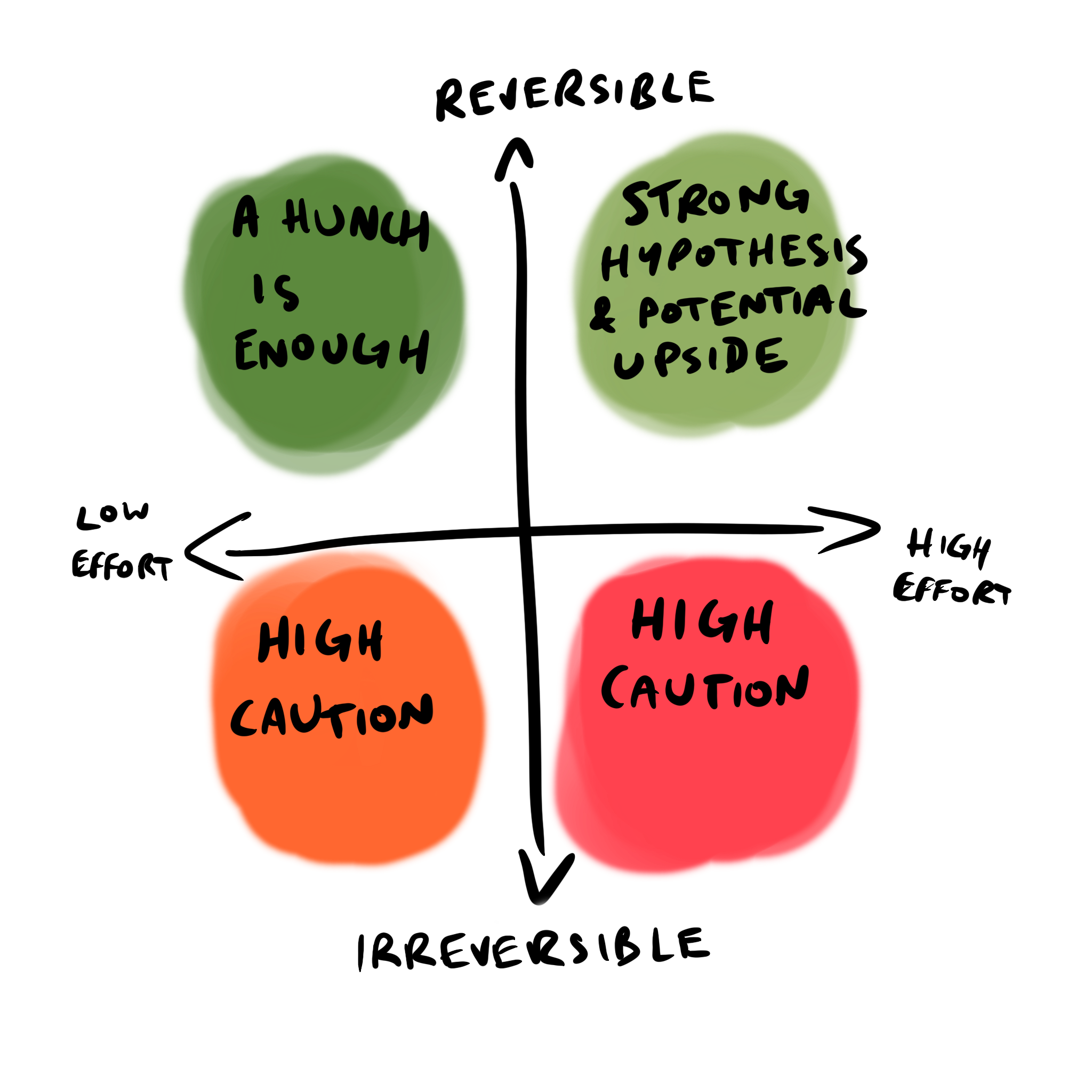

Jeff Bezos frames decisions as either “one way doors” that require careful deliberation and consultation or “two way doors”; decisions that can be reversed. Most fall into the second category. Saying that he’s been wildly successful following the model is something of an understatement.

A decision that pays off will make an enormous difference, but even the aggregation of small experiments builds up to something significant. In contrast, arduous processes and cycles that consume time and resources cost a fortune and land you with the cost of delay in carrying out a change as well the loss of any benefit from the knowledge a failed experiment imparts. There’s time for fast decision making, and there’s time for careful consideration; the advantage is in knowing which to utilise in the moment.

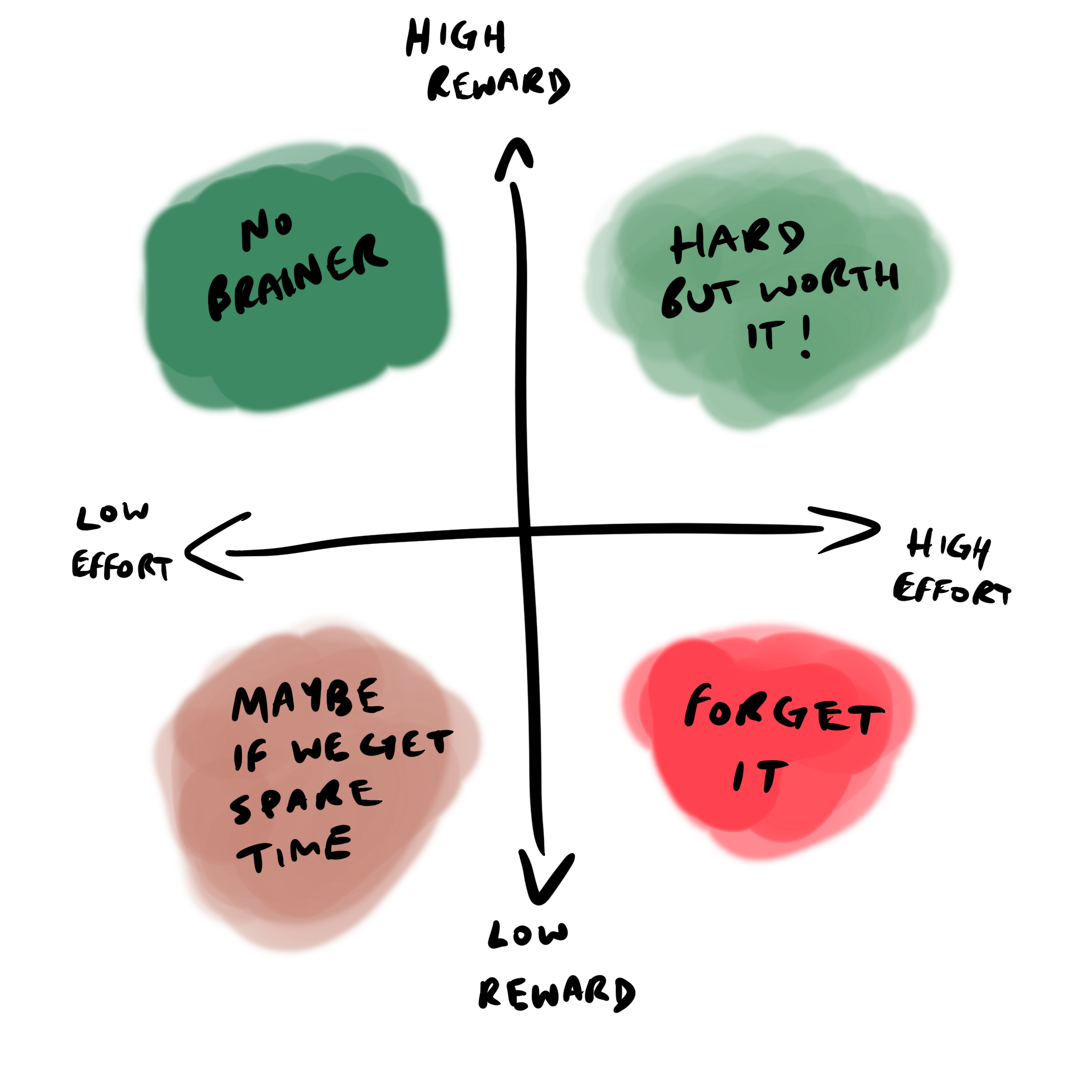

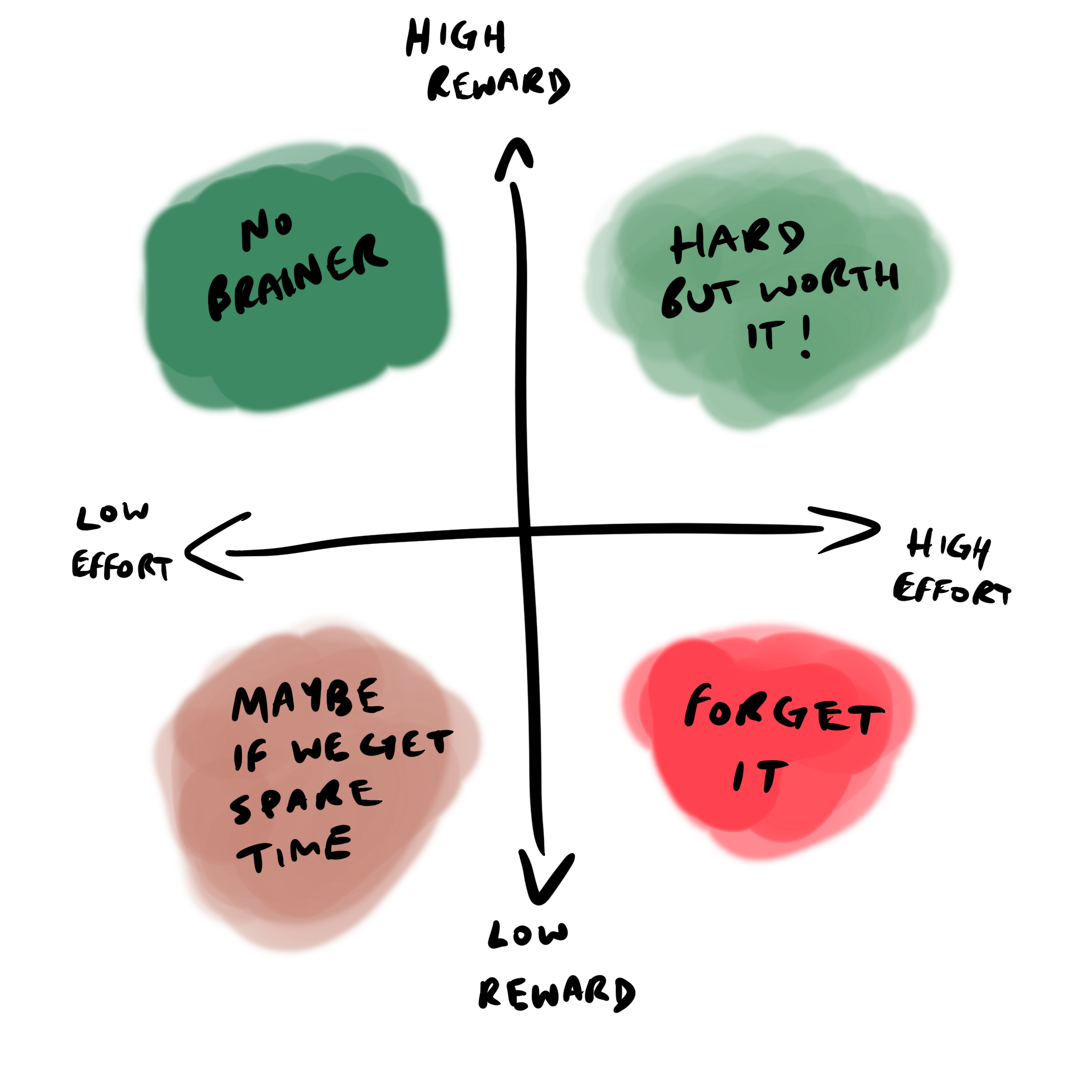

In business a simple effort vs reward matrix can be used to decide what to focus on. They typically look like the one below. Low effort, high reward activities are no brainers, cherish these. If something requires a lot of effort but pays off well then that’s usually next in priority. Low effort and low reward activities are left to do only if there’s time to spare. High effort low reward should be left to the suckers, forget it.

Another dimension that we need to consider is potential upside (positive) vs downside (negative). Whilst the former is essentially the reward axis, there is no representation of the potential downside on the diagram.

We can think about effort vs reversibility in the same way and equally we need to consider potential upside and downside. An effort vs reversibility matrix allows the separation of things you need to be cautious about from things that you should just get on with. Framing decisions in this way provides a rule of thumb for:

In practice I’ve used this approach to make decisions quickly which on the surface may have seemed reckless. If the changes hadn’t worked it would have been relatively easy to reverse. As an example, working in telecoms I had to respond to my team growing overnight to 18 people as we merged with another. Using Scrum the team size was far from ideal (cognitive load and the number of communication paths). We could have done nothing and trundled along. We didn’t spend weeks building consensus with stakeholders, running through process diagrams or debating every possible scenario. Almost instantaneously we decided (1) to go fully remote and (2) to work as two sub-teams with a couple of light touch processes to keep in sync. The changes happened within a week (which in a large corporate is almost instantaneous) and with the result of moving quickly there was no loss of momentum on the work in progress.

Once you start looking at decisions as either reversible or irreversible it becomes easier to be someone who makes things happen. You’ll know it when you have to dig a bit deeper to find patience with people that don’t move as fast. If something is easily reversible, you just decide and move on.

When something is reversible, it’s a lot easier to be bold.